ENGLISH version

PRINT

FLYER

8x11

PDF (511k)

CLICK

HERE

5x8

2-up PDF

(566k)

CLICK

HERE

Scroll down for more information... Click

here for Panelists • Maps • Spanish

flyer

Please note location change!

|

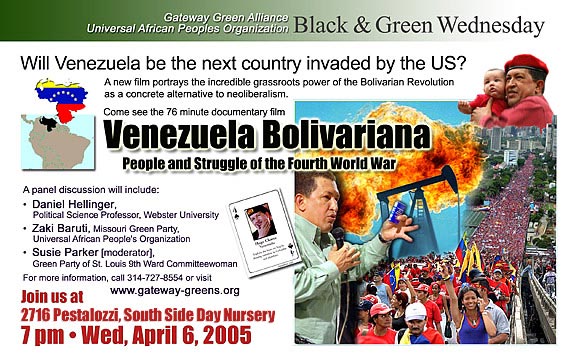

Black & Green Wednesday Forum

Venezuela Bolivariana People and Struggle of the Fourth World War |

WHEN: 7 pm, Wednesday, April 6, 2005

WHERE: 2716 Pestalozzi (this is a location change)

South Side Day Nursery

St. Louis MO 63118Will Venezuela be the next country invaded by the US?

Come see and discuss the 76 minute documentary film:

Venezuela Bolivariana: People and Struggle of the Fourth World War.A panel discussion will include:

Dan Hellinger,

Political Science Professor, Webster UniversityZaki Baruti,,

Missouri Green Party, Universal African Peoples OrganizationSusie Parker [moderator],

Green Party of St. Louis

21st Ward CommitteewomanSponsored by the Gateway Green Alliance and the Universal African Peoples Organization. For more information call 314-727-8554.

Venezuelan's Bolivarian Revolution in Year Six

by Daniel Hellinger

In 1982, a Venezuelan Lt. Colonel, Hugo Chávez, and a group of comrades swore an oath to one another to replace the government of the day with one more faithful to the ideas of Venezuela's great independence leader, Simón Bolívar. They were angry at the corruption and waste of the country's huge oil resources. Although Venezuela was an electoral democracy, they felt that the leaders of the two major political parties had made elec-tions meaningless.

The 1980s were a time of economic hardship for most Venezuelans. After a decade long oil boom, prices had col-lapsed. In 1989, the population revolted when President Carlos Andrés Pérez tried to impose a set of austerity measures demanded by the International Monetary Fund. In 1992, Chávez's military conspiracy tried but failed to overthrew Pérez. Although polls showed Venezuelans wanted no part of dictatorship, mass demonstrations broke out in solidarity with Chávez, who claimed his goal was to rescue Venezuela's democracy from the corrupt politicians.

By December 1998, Chávez, having served a short time in prison after the coup, had built an electoral movement that not only put him in the presidency but gave him the power to re-write the Constitution. The new charter renamed the country the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Chávez also used his power to lead a reinvigorated Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and put the state oil company back under control of the government.

These political changes and diplomatic success laid the base for Chávez to announce, under authority granted by the elected National Assembly, a sweeping series of decrees that began a process of urban and rural land reform, raised taxes and royalties paid by foreign oil companies operating in Venezuela, created popular banks to stimulate coopera-tives, and several other popular programs. These measures galvanized his opponents, mostly owners of the media, oil executives, business owners, the old political class, and some labor leaders associated with the former era. In response, Chávez launched a series of missions, some led by the army, aimed at improving housing, education and health in the barrios. Some 15,000 Cuban medical personnel helped with the health project.

The opposition, supported by the United States, tried to oust the president through strikes, civil disobedience, and even a coup. The coup, in April 2002, failed when poor Venezuelans and loyal military units rallied to the president's side, after he was held prisoner for two days. Finally, the opposition tried a legal route - a recall election. But on August 15, 2004, Chávez won 59% of the vote and repelled the challenge.

Chávez's Bolivarian Revolution enjoyed enhanced legitimacy as it entered 2005. The economic outlook is promis-ing, though sustaining growth at the estimated pace of 16% may be difficult. The traditional opposition is divided and demoralized. Now grassroots activists are impatient for the president to make good on the more participatory democ-racy that he promised when the new Constitution was written in 1999, and there are signs that the president has heeded the call.

High oil prices have helped economic recovery. In the longer run, the success of the Bolivarian Revolution depends upon dividends from public investment in human capital (health and education) and grassroots economic initiatives, e.g., weaning Venezuelans off Big Macs and onto traditional arepas and cachapas, made from corn meal. Emphasis is being placed upon creating cooperatives producing agricultural and light manufacturing goods, attracting people back into farming in the countryside, and expanding industries (petrochemicals) linked to the oil industry. These bold ex-periments may send the economy crashing in a few years or make Venezuela an alternative economic model for the Third World.

On the other side of the coin, some administrators, especially those drawn from the military, have engaged in cor-ruption or displayed an authoritarian streak. Recent threats made by an oil minister and a military commander against a prominent ecologist who has criticized coal mining operations show the dangers.

Although the chavistas nearly swept regional elections in October, some political vulnerability was exposed. Levels of abstention rose from 30 to 54%. Many grassroots activists who delivered "no" votes on August 15 were angry that candidates for state and local offices were imposed from above at the direction of Vice President José Vicente Rangel. Chávez's party, the Fifth Republic Movement (MVR), promises to do better for municipal elections and congressional elections later this year. In February, the MVR announced a system of quotas designed to ensure that half of all candi-dates are women and to respect the wishes of community leaders.

Until recently, most of Chávez's programs have re-directed oil earnings toward the poor, but not touched accumu-lated wealth. Now, with urban and rural land reform, regulation of the private media, creation of a cooperative sector to compete with private businesses, extension of free medical services to sectors served by private doctors, and other current initiatives, chavismo is clashing even more with propertied interests.

There are increased signs of popular organizations taking matters into their own hands. Workers recently seized the VENEPAL paper factory in the industrial city of Valencia. There have been reports of land seizures in other parts of the country. To this point, the government has backed the workers. In Chile during the Allende years (1970-1973), these kinds of seizures led to further political polarization and economic disruptions. Venezuela's oil-fueled economy probably is less vulnerable to economic pressure, but the United States shows signs of hoping to exploit tensions and have Chávez meet the same fate as Allende, who was deposed and died in a coup in 1973.

Chávez is fast becoming a revolutionary icon, a worldwide symbol of resistance to neoliberal globalization and per-haps the most popular and influential leader in Latin America, exceeding even Fidel Castro in these respects. That Chávez has continued to advance a revolutionary agenda rather than opportunistically consolidating his own personal power is to be admired, but there are several cautions to keep in mind.

Opportunistic elements remain within chavismo. Some recently elected governors and mayors are politicians who simply shifted from the old, discredited parties of the past to the MVR. Although there are many dedicated community leaders in the chavista ranks, some Bolivarian leaders are practicing the discredited cronyism of the past, making mem-bership in Bolivarian Circles a condition for getting small loans or food subsidies. There is a danger that the revolution could ossify and become little more than a patronage machine with new faces.

The army remains a major component of chavismo. In Zulia, human rights activists were joined by local demo-cratic leaders, supporters themselves of Chávez, to call upon the army to stop threatening local environmentalists con-cerned about plans to increase coal mining in the Andes.

And then there is the murky relationship between Chávez and the FARC guerrillas of Colombia. During his period in the political wilderness in the 1990s, there is little doubt that Chávez enjoyed good relations with the FARC. The tactics of the FARC include kidnapping and taxation of narcotics trafficking. The FARC is guilty of well-documented human rights abuses, although not on the scale of the right wing death squads and Colombian military. Recently, Venezuelan police hired by Colombian operatives kidnapped the FARC foreign minister off the streets of Caracas, causing severe strains in relations between the two countries, something that the United States hopes to exploit.

The Venezuelan government's human rights record is remarkably positive given the irresponsible behavior of the opposition and the extreme political polarization. However, there is little doubt that high oil prices have cushioned the economy and capitalized the social programs that are improving people's lives. The challenge is make these programs sustainable without oil subsidies and to preserve the impressive democratic innovations of the Bolivarian Revolution.

Daniel Hellinger is a Professor of Political Science at Webster University.