PRINT

FLYER

8x11

PDF (627k)

CLICK

HERE

5x8

two-up PDF (617k)

CLICK

HERE

For best sizing without extra margin space, print with "Fit to Page" unchecked.

Scroll down for more information...

Click for Confluence article --> Mommy,

the Rice Puffs Gave Me the Finger!

|

Black

& Green Wednesday Forum

Human Genes in our FOOD? |

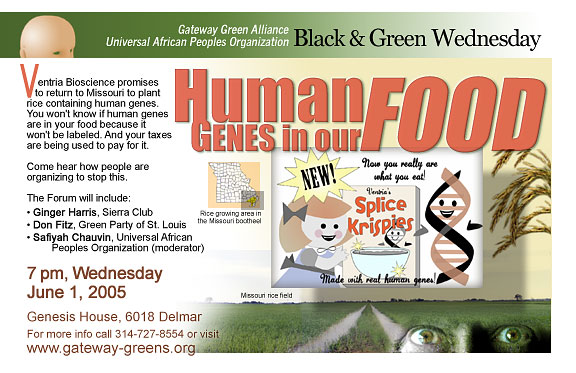

WHEN: 7 pm, Wednesday, June 1, 2005

WHERE: Genesis House

6018 Delmar (east of Skinker)

St. Louis MOVentria Bioscience promises to return to Missouri to plant rice with human genes. Human genes are being spliced into both animals and plants. You won't know if human genes are in your food because it won't be labeled. And your taxes are being used to do it. Come hear how people are organizing to stop this.

A panel discussion will include:

Ginger Harris, Sierra Club

Don Fitz, Green Party of St. Louis

Safiyah Chauvin [moderator], Universal African Peoples Organization

Sponsored by the Gateway Green Alliance and the Universal African Peoples Organization. For more information call 314-727-8554.

Mommy, the Rice Puffs Gave Me the Finger

By Don Fitz

Published by Confluence at http://www.stlconfluence.orgWould it be worse to find a finger in your chili or guzzle human DNA when you down a beer? In the recent furor over the potential for "pharmed" rice to destroy Missouri's rice growing industry, something is being downplayed: corporations are proposing to put human DNA into plants whose neighboring cousins could end up being eaten (or drunk) by people.

Ever since Ventria Bioscience announced its intentions to plant genetically engineered rice, it faced strong opposition from environmentalists and local rice farmers. "Pharming" is an experimental method of inserting human or animal genes into plants so they will become biofactories for producing pharmaceuticals. Ventria claims that its pharmed rice would produce the proteins lactoferrin and lysozyme, which would go into medicines for dehydration and diarrhea. But Friends of the Earth spokesperson Bill Freese says that Ventria is just as likely to use its rice to make granola bars, yogurt or poultry feed.

In 2004, Ventria's application to pharm 120 acres of rice in California was turned down. Seeking a state with even less environmental concern than that governed by Arnold, the company looked to John Ashcroft's Missouri. Its politicians readily promised support and $30 million in subsidies.

The Missouri project would allow up to 204.5 acres of such rice to be grown. It would not only be the largest pharmed crop in the world - it would dwarf the typical pharmaceutical crop of less than an acre.

Rice farmers are not at all happy with the idea of such a large field being planted next to theirs. If the pharmed rice spreads, it could contaminate their fields. Pharmaceutical rice could be spread by cross-pollination, floods, rice-eating birds, rice grains in farm equipment, or human error in distribution. Risks from pharmed rice include allergic reactions, aggravation of bacterial infections and auto-immune disorders.

Farmers might be less nervous if Ventria had liability insurance. But instead of purchasing enough insurance, Ventria has its public relations artists spin the yarn that dangers are too little to worry about. "It can't happen here" is the essence of its message.

But it has happened. The StarLink corn incident of 2000 led to a $1 billion recall. In 2002, a half million bushels of soybeans in Nebraska had to be destroyed. Iowa burned 155 acres of pharmaceutically contaminated corn.

As Ventria was touting the pharming of its rice as risk-free, on the other side of the globe Greenpeace campaigner Sze Pang Cheung announced the illegal release of genetically contaminated rice in China. That Bt rice that could cause allergic reactions in people.

The gnawing question remains. Doesn't Ventria's arguing that accidents never happen instead of showing that it has insurance to cover accidents suggest that the company doesn't believe its own press releases?

The Missouri chapter seemed like it might be over when Anheuser-Busch announced on April 12 that it would not buy Missouri rice if genetically engineered rice were grown in the state. Like Monsanto, Busch is headquartered in St. Louis. Busch is both the largest brewer and the biggest purchaser of rice in the country.

As soon as the beer threat hit the news, Missouri politicians repeated their act of falling over each other while rushing to serve the genetic engineering industry. Just three days later, Governor Matt Blunt announced that a deal had been brokered between Busch and Ventria. The beer giant would drop its threat to boycott Missouri rice and Ventria would promise that its pharmed rice would be grown at least 120 miles from other Missouri rice fields.

As the politicians patted themselves on the back, Missouri rice growers maintained their doubts. The rumor went out that Ventria plans to get a field near Mark Twain's home town of Hannibal in the northern part of the state. But it might not be as easy to pharm rice in northern Missouri as it is in the boot heel, the state's southernmost region. Farmers have a strong suspicion that once Ventria gets its foot in Missouri's door and the controversy is out of the news, the corporation will slither down the Mississippi to the state's prime rice-growing fields.

On April 29, Mother Nature rewarded the steadfastness of farmers and environmentalists. To the chagrin of politicians, Ventria announced it was putting the lid on planting rice in Missouri during 2005. The required permit from the Agriculture Department could not arrive until after May 20, the last day for planting rice in the state. But the company's president promised that Ventria would return to Missouri in 2006.

There is a deeper side to this story that is being sidestepped: Why would sales plummet if pharmed rice genes got into regular rice? Part of it is the risk to public health. But reporters are not asking people who eat rice (virtually all of us), "Do you want to have human genes in what you eat and drink?"

Perhaps beer drinkers are not the only ones who don't want to taste a little bit of Uncle Fred. Maybe mommies don't want to give their darlings wee morsels of Aunt Sally in their rice puffs before waving them off to school.

This brings to mind a problem which plagued the meat packing industry a century ago. Upton Sinclair wrote in The Jungle that sometimes packinghouse workers "...fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting,-sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham's Pure Leaf Lard!"

Most people would see gobbling up a finger in a bowl of chili as cannibalism. But what about the tip of a finger? If you eat food cooked with lard which includes fragments of a slaughterhouse worker, is that cannibalism?

Is it cannibalism to eat food with one human gene? What about 50 human genes or an entire human chromosome?

To use the language of the genetic engineering industry, we could say that human DNA in rice is "substantively equivalent" to human flesh in hamburger meat or human remains in Durham's Lard. Of course, there are differences. Genes are incredibly small in comparison to boiled human flesh. But those human genes would be present in every cell of every contaminated plant you put into your mouth.

This is not something that suddenly arose with Ventria rice in Missouri's boot heel. Genetic engineering researchers have been putting human genes into animals for years for medical purposes, such as trying to make pig hearts human-compatible. Gen Pharm bioengineered Herman, the first transgenic dairy bull, for siring cows that produce milk with a human protein.

Scientists with the US Department of Agriculture put human growth hormone genes into pig embryos to produce faster growing hogs. The project did not stop because its originators woke up at night pondering the morality of what they were doing. Rather, it was abandoned because the resulting pigs were so deformed that some could not support their own weight.

But other laboratories could well overcome these failures and successfully implant even more human material into plants and animals. If one gene worked pretty well, could 20, 100 or 1000 genes work even better? In 1997, Japanese researchers reported inserting a complete human chromosome into mice to produce human antibodies.

How much human material spliced into a living organism makes its products "essentially human?" This ethical dilemma is deafening by the silent treatment it is given by such great moral leaders as John Kerry and George W. Bush.

Imagine that you doze off one night while watching Buffy slay the bad guy. You wake up thinking you heard an ad for "Angel Beer" that is fortified by inserting genes from human blood into rice that's sold to the brewery. It might be hard to tell if it was a nightmare or the latest biotech venture into Missouri's boot heel.

Eating food with human genetic components would certainly run counter to the moral or religious beliefs of many people. Even those who do not share their views are likely to defend their right to practice their beliefs. Clearly, all genetically contaminated food should be labeled so that those who choose not to consume it can do so. But the last thing you are likely to see on any bottle of beer, box of rice puffs, pharmaceutical, or lard is a statement that "This contains human by-products or genetic material."

What this means in the realpolitik of pharming is that if the biotech industry gets its way, there may soon be human DNA in every rice product on the shelf. Once human genes get into a plant, they become a permanent part of that species. When Grandpa is spliced into a pollinating plant, he just keeps blowin' in the wind forever. His DNA becomes part of the diet of all who eat the plant. Unlike exploding gas tanks, Grandpa's genes can't be recalled.

People may or may not agree that consuming food, drinks or drugs with human DNA is cannibalism. One thing that politicians and biotech companies firmly agree on is that those who have these ethical concerns must not have the right to know what is in their food. Maybe Wendy's is not responsible for that finger reportedly found in the bowl of chili. Instead of Wendy's, it seems that the biotech industry is the one giving the finger to the American public.

Don Fitz is on the National Committee of the Green Party USA and is Outreach Coordinator for the Missouri Green Party. He can be reached at fitzdon@aol.com.